Fall Risk Medication Calculator

Medication Assessment

Select medications that increase fall risk

Results & Recommendations

Every year, over 36 million older adults in the U.S. fall - and nearly 32,000 of them die from it. Falls aren’t just accidents. For many, they’re the direct result of medications meant to help but instead leave them unsteady, dizzy, or confused. The culprits? Common sedating drugs like benzodiazepines, antidepressants, opioids, and muscle relaxants. These aren’t rare prescriptions. They’re everyday treatments for insomnia, anxiety, pain, and muscle spasms. But when stacked together - as they often are in older adults - they turn a simple walk to the bathroom into a life-threatening risk.

What Makes a Medication a Fall Risk?

Not all sedating drugs are created equal, but they all share one dangerous trait: they slow down the brain and body just enough to throw off balance. The list of medications linked to higher fall risk is long and includes:

- Benzodiazepines (like diazepam or lorazepam) - used for anxiety or sleep, but they cause drowsiness and impaired coordination.

- Antidepressants - especially tricyclics and SSRIs with sedating effects. Taking two or more increases risk sharply.

- Opioids - even moderate doses can cause dizziness and mental fogginess.

- Antipsychotics - often prescribed for dementia-related behaviors, but they significantly raise fall risk.

- Baclofen - a muscle relaxant with the highest documented fall risk in its class.

- Antihypertensives - blood pressure meds that drop pressure too fast, causing lightheadedness when standing.

The real danger isn’t just one drug. It’s polypharmacy - taking three or more medications at once. Each additional pill increases fall risk by 10-20%. A 78-year-old on a sleeping pill, a painkiller, an antidepressant, and a blood pressure med isn’t just managing symptoms. They’re walking a tightrope.

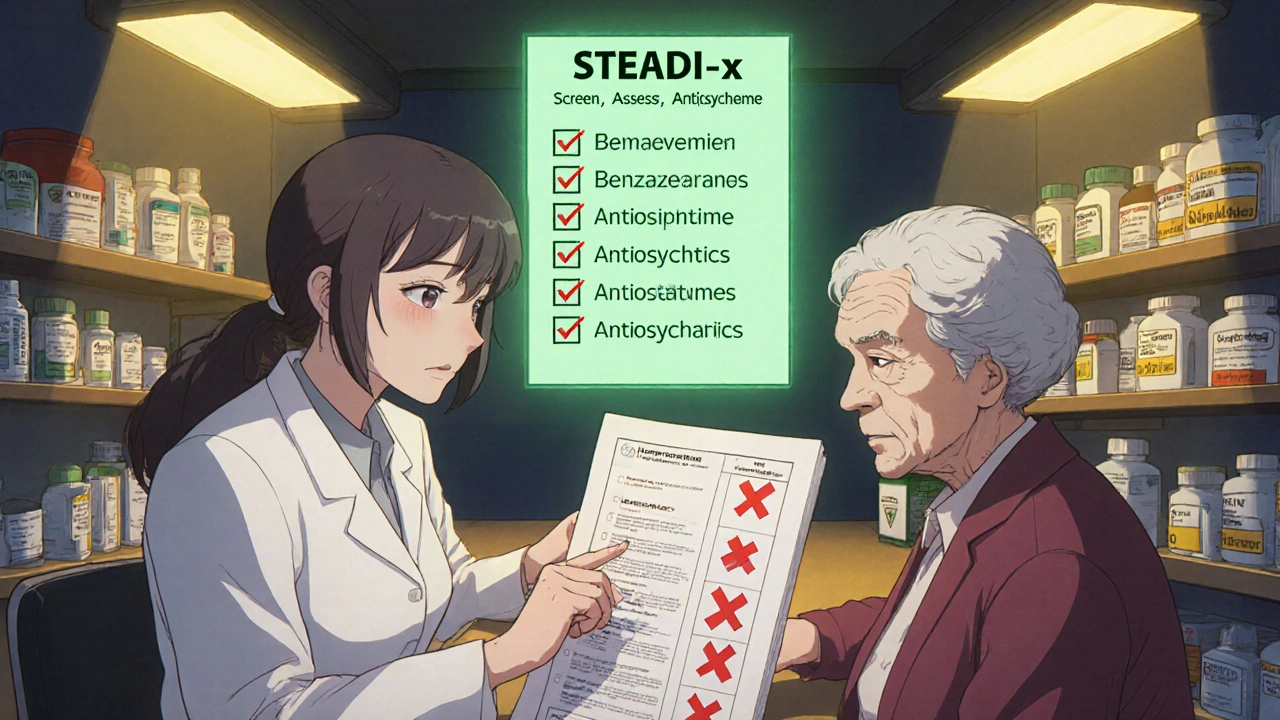

The STEADI-Rx Approach: A Proven System

The CDC’s STEADI-Rx program isn’t a suggestion - it’s a blueprint. Developed by the University of North Carolina and rolled out in pharmacies nationwide since 2019, it gives healthcare teams a clear, step-by-step way to cut medication-related falls. It’s simple: Screen, Assess, Intervene.

- Screen - Use a quick tool to identify who’s at risk. Ask: Have you fallen in the past year? Do you feel unsteady? Do you take four or more medications?

- Assess - Dig into the medication list. Look for FRIDs (Fall Risk Increasing Drugs). Check for duplicates, unnecessary prescriptions, or doses that are too high.

- Intervene - This is where change happens. Pharmacists work with doctors to:

- Switch to safer alternatives - like non-sedating sleep aids or SNRIs instead of tricyclic antidepressants.

- Lower doses - especially for opioids and benzodiazepines.

- Stop drugs that aren’t helping - 75% of STEADI-Rx recommendations involve switching or removing a medication.

One study found that using this model could prevent over 42,000 medically treated falls each year and save $418 million in healthcare costs. That’s not theory - it’s happening in community pharmacies right now.

Medication Review Alone Isn’t Enough

Stopping a sedating pill helps - but it’s not a magic fix. The strongest results come when medication changes are paired with movement. The Cochrane Review analyzed over 100 studies and found that exercise programs reducing falls by 15-29% were the most effective intervention. Not just any exercise. These programs focused on:

- Balance training - standing on one foot, heel-to-toe walking.

- Strength work - leg lifts, chair stands, resistance bands.

- Gait training - walking with proper posture and rhythm.

People who did 30-90 minutes of this, 1-3 times a week for at least 12 weeks, cut their risk of falling and breaking a bone by over 60%. Even better, combining medication review with exercise cut fall rates more than either alone.

Vitamin D? The evidence is mixed. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends 800 IU daily, but some reviews found no benefit. It’s not a bad idea, but don’t count on it as your main defense.

Real Stories: What Works and What Doesn’t

On Reddit’s r/geriatrics forum, users share hard-won wins. One man, 81, switched from diazepam to cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia. His nighttime falls dropped from 2-3 per month to zero in six months. Another woman replaced her opioid painkiller with physical therapy and acupuncture - her dizziness vanished.

But not everyone has that success. A 2021 survey by the National Council on Aging found 63% of older adults struggled to stop sedating meds. Why? Fear. Withdrawal. Doctors who won’t let go. One woman said, “My doctor said if I quit the sleep pill, I’d be worse off. But I was falling every week. I had to switch doctors to get help.”

Pharmacists say they see this all the time. An 82% majority believe medication reviews reduce falls, but only 45% feel they have enough time to do them right. Time is the enemy. A 10-minute visit won’t cut it. You need 30-45 minutes to review a full med list, talk to the patient, and coordinate with the prescriber.

How to Start Making Changes

If you or a loved one is on sedating medications, here’s how to take action:

- Get the full list - Write down every pill, patch, and liquid. Include over-the-counter drugs like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) - a hidden fall risk.

- Ask the pharmacist - Request a medication therapy review. Many pharmacies offer this for free, especially if you’re on Medicare Part D.

- Ask the doctor - “Is this medication still necessary? Is there a safer alternative?” Don’t be afraid to push.

- Start moving - Sign up for a fall prevention class at a local Y, senior center, or physical therapy clinic. Look for programs labeled “Tai Chi for Arthritis” or “Otago Exercise Program.”

- Track progress - Keep a simple log: “Fell on [date]? What meds were taken? How was balance that day?” Patterns will show up.

And if your doctor resists changing a prescription? Ask for a referral to a geriatrician or a pharmacist with geriatric training. These specialists know how to safely taper off sedating drugs without triggering withdrawal or rebound symptoms.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters Now

The U.S. population over 65 will hit 80.8 million by 2040. That’s one in five Americans. Every one of them is at risk. The CDC’s STEADI initiative is now used by 78% of state health departments and 65% of major health systems. The Beers Criteria - updated every three years by the American Geriatrics Society - now lists over 50 medications that should be avoided or used with extreme caution in older adults.

But progress is slow. Reimbursement for medication reviews is still patchy. Many doctors don’t know how to deprescribe. Patients are scared to stop pills they’ve taken for years. The system isn’t built for prevention - it’s built for reaction.

Change starts with asking one question: “Could this medicine be making me less safe?” If the answer is yes, then the next step isn’t more pills. It’s less. And movement. And support.

What are the most dangerous sedating medications for older adults?

The highest-risk medications include benzodiazepines (like diazepam), tricyclic antidepressants, opioids (especially at high doses), antipsychotics, and muscle relaxants like baclofen. These drugs slow reaction time, cause dizziness, and impair balance. Even over-the-counter antihistamines like diphenhydramine (Benadryl) are risky and should be avoided in older adults.

Can stopping a sedating medication really reduce fall risk?

Yes - and often dramatically. Studies show that switching from a benzodiazepine to a non-sedating alternative can cut nighttime falls by 70-80%. One large study found that 75% of successful interventions involved replacing or removing a sedating drug. The key is doing it safely, with a plan to manage withdrawal symptoms and replace the medication’s function with non-drug strategies like therapy or sleep hygiene.

How often should older adults have their medications reviewed?

At least once a year - and every time there’s a new diagnosis, hospital stay, or change in health. Older adults on four or more medications should have a review every six months. Pharmacists are trained to spot dangerous combinations and unnecessary prescriptions. Ask for a Medication Therapy Management (MTM) session if you’re on Medicare Part D - it’s free.

What kind of exercise helps prevent falls the most?

Balance, strength, and gait training work best. Programs like Tai Chi, Otago Exercise Program, or physical therapy sessions focused on standing on one foot, heel-to-toe walking, and chair stands are proven to reduce falls by 15-29%. Aim for 30-90 minutes, 1-3 times per week, for at least 12 weeks. The goal isn’t to get stronger overall - it’s to improve stability while standing, turning, and walking.

Who can help me review my medications for fall risk?

Your pharmacist is your best first stop - especially one trained in geriatric care. Many community pharmacies offer free medication reviews. You can also ask your doctor for a referral to a geriatrician or a certified geriatric pharmacist. Look for credentials like BCPS (Board Certified Pharmacotherapy Specialist) or GCS (Geriatric Certified Specialist). These professionals know how to safely deprescribe and coordinate care.

Reviews

Man, I never realized how many of my grandpa’s meds were basically fall traps. He’s on five things, including that damn Benadryl for ‘allergies’ - turns out it’s just making him wobble like a toddler. We just got him off the diazepam and into CBT-I, and he hasn’t fallen in three months. No more midnight bathroom faceplants. Small wins, but they matter.

It’s not merely polypharmacy-it’s pharmacokinetic drift compounded by age-related hepatic and renal clearance decline. The Beers Criteria are empirically robust, yet clinical inertia persists due to fragmented care pathways and inadequate reimbursement for deprescribing. The STEADI-Rx framework is methodologically sound but underutilized owing to systemic disincentives.

Oh my heart 🥺 I just read this and thought of my mom-she’s 79 and on 7 meds, including one for ‘sleep’ that makes her forget where the stairs are. I’m taking her to the pharmacist next week for a review. She’s scared to stop anything, but I told her: ‘Mom, if your meds are making you scared to walk, they’re not helping-they’re hurting.’ We’ve got this 💪

Thank you for this comprehensive overview. The integration of medication review with structured exercise programs represents a paradigm shift from reactive to proactive geriatric care. The evidence base is unequivocal: multimodal interventions yield superior outcomes. Healthcare systems must prioritize funding for pharmacist-led MTM and community-based balance programs.

India’s got the same problem, but worse. Grandmas on sleeping pills and painkillers, no one checking. Pharmacies sell benzodiazepines like candy. We need community health workers to walk door to door with med lists. No fancy tech-just people asking, ‘Beta, what are you taking?’

It’s ironic, isn’t it? We give these drugs to soothe the mind, but they fracture the body. We treat anxiety with chemicals that induce tremors. We silence insomnia with substances that mute proprioception. We’re not healing-we’re trading one suffering for another, and calling it medicine. The real question isn’t ‘Which drug?’ but ‘Why are we so afraid of stillness?’

Of course, the CDC has a program. Of course, the Beers Criteria exist. And yet, my 80-year-old neighbor is still on lorazepam, hydrocodone, and amitriptyline-all prescribed by the same doctor who also gave her a flu shot and a coupon for a weight-loss shake. This isn’t healthcare. It’s pharmaceutical theater. The real epidemic isn’t falls-it’s the cult of the prescription.

My dad’s pharmacist noticed he was on two sedating antidepressants. One was for depression. The other? For ‘neuropathic pain’-but he had no neuropathy. They switched him to duloxetine and cut the dose of the other. He’s been walking without a cane for six months now. It’s not magic. It’s just attention.

This is the kind of post that makes me believe change is possible. I’ve seen elders in my village take 10 pills a day because ‘the doctor said so.’ But when we started a weekly chai-and-check group with the local nurse, three people stopped their sleep meds. One guy started doing chair yoga with his grandkids. He says he feels like he’s 50 again. Let’s build more of these spaces

Oh, so now we’re blaming the meds? What about the fact that 80-year-olds still think they can climb ladders to change lightbulbs? Maybe the problem isn’t the benzos-it’s the delusion that they’re still 35. I’ve seen grandmas fall because they refused to use a walker. But sure, let’s take away their pills and call it a win.

The entire premise is bourgeois. You assume agency exists where none does. An elderly person on Medicaid doesn’t ‘ask for a pharmacist review’-they wait for the system to notice them. The real solution? Abolish the medical-industrial complex. Until then, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic while the pills keep flowing.

It is imperative that we recognize the profound societal implications of medication-induced fall risk among the geriatric population. The demographic transition underway in both developed and developing nations necessitates a paradigmatic shift in clinical practice. The integration of non-pharmacological modalities, particularly structured balance and strength training, must be institutionalized as a standard of care. Moreover, the role of the pharmacist as a primary care coordinator in geriatric medication management is not ancillary-it is foundational. We must advocate for policy reforms that enable adequate time, reimbursement, and interprofessional collaboration to ensure that the dignity and safety of our elders are not compromised by outdated prescribing habits.