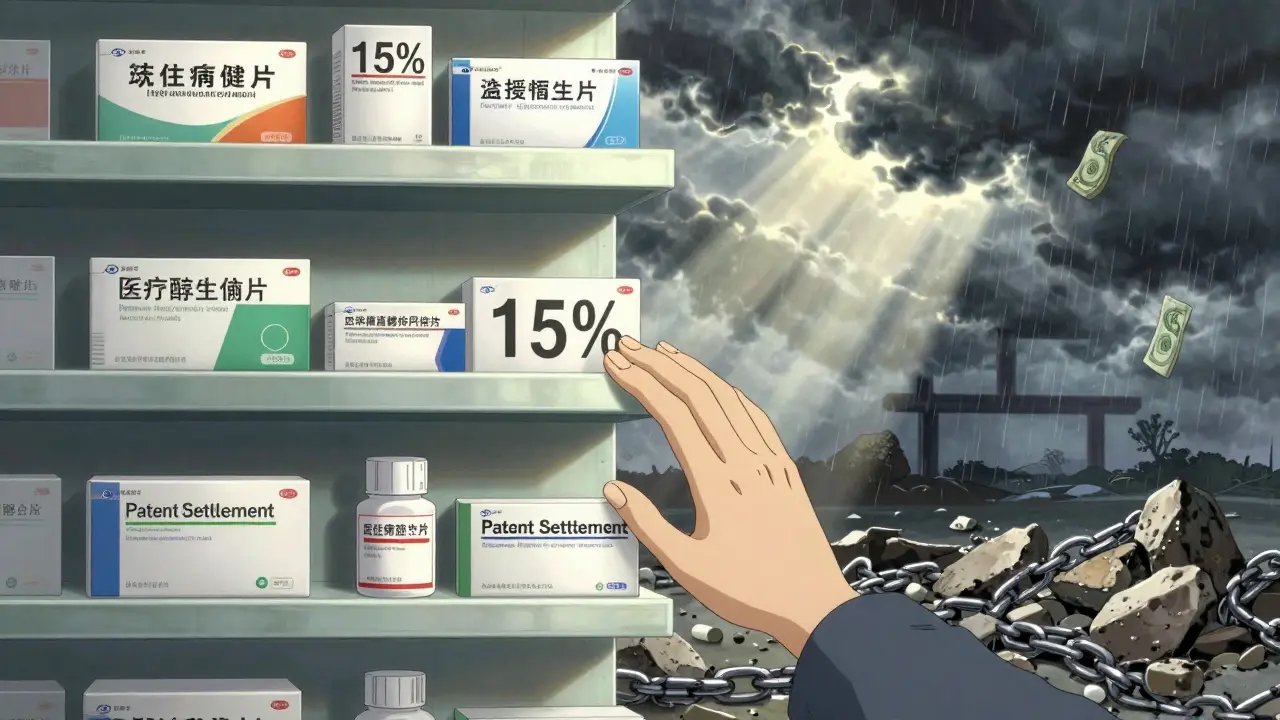

When a brand-name drug’s patent is about to expire, the expectation is simple: generic versions flood the market, prices drop, and patients save money. But in reality, something else often happens-authorized generics appear, not from independent manufacturers, but from the very company that made the original brand drug. These aren’t knockoffs. They’re identical pills, same factory, same ingredients, just repackaged with a generic label. And they’re changing how competition works-often in ways that hurt patients and independent generic makers.

What Exactly Is an Authorized Generic?

An authorized generic is a version of a brand-name drug sold under a generic name, but made by the original manufacturer-or a company they license it to. It’s not a new drug. It doesn’t need new FDA approval. It’s the same tablet, same capsule, same batch, just labeled differently. The FDA allows this because the Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 never said it was illegal. But it wasn’t meant for this.

Think of it like this: You buy a popular soda. Then, the soda company launches a cheaper version with a different label, same formula, same distributor. Only now, instead of letting a rival company undercut them, they’re undercutting themselves-and keeping the profit.

The Hatch-Waxman Act Was Supposed to Help Generics

The Hatch-Waxman Act was designed to balance two things: protecting innovation and speeding up access to affordable drugs. It gave the first generic company to challenge a patent a 180-day exclusivity window. During that time, no other generic could enter the market. That’s a huge incentive. It’s how companies like Teva and Mylan built their businesses-by taking legal risks to knock out patents and then reaping the rewards.

But here’s the twist: the law never said the brand company couldn’t launch its own generic version during that 180-day window. So they started doing it. And when they did, the first generic company didn’t get to monopolize the market. Instead, they had to split it-with a product that cost the same as the brand.

How Authorized Generics Crush Generic Competition

Without an authorized generic, the first-filer generic typically captures 80-90% of the market during its exclusivity period. Prices drop fast. Patients pay pennies. Pharmacies and insurers save millions.

With an authorized generic? That number drops to 40-50%. Why? Because the authorized generic doesn’t price like a real generic. It doesn’t drop 80% like independent generics do. It’s priced just below the brand-say, 15-20% cheaper. That means patients and insurers still pay a lot. And the independent generic? They’re stuck in the middle, trying to compete with a product that’s identical to the brand but cheaper than their own.

The FTC found that when an authorized generic enters, the first generic’s revenue drops by 40-52% during the exclusivity window. Even three years later, those companies still earn 53-62% less than they would have without the authorized generic. That’s not competition. That’s sabotage.

Reverse Payments and Secret Deals

The worst part? These authorized generics aren’t always spontaneous. Often, they’re part of a secret deal.

In patent litigation, a brand company might be losing in court. Instead of letting a generic enter and take over, they strike a deal: "You drop your lawsuit, and we won’t launch our own generic." That’s called a "reverse payment." The brand pays the generic to stay out. And sometimes, the payment isn’t cash-it’s a promise not to launch an authorized generic.

Between 2004 and 2010, about 25% of patent settlements involved these kinds of agreements. They delayed generic entry by an average of 38 months. That’s over three years of monopoly pricing. And it affected drugs worth more than $23 billion.

The FTC calls this the most egregious form of anti-competitive behavior in pharma. Courts have started cracking down. But the practice didn’t vanish. It just got sneakier.

Who Benefits? Who Gets Hurt?

Branded drug companies win. They keep control of the market. They avoid the full price drop. They even get to charge premium prices under a different label.

Independent generic manufacturers lose. Teva reported a $275 million revenue hit in 2018 from just one authorized generic. Smaller companies? They can’t survive that kind of blow.

Patients? They pay more. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) might like authorized generics because they add another pricing tier-but that doesn’t mean patients save. In fact, IQVIA data shows that in markets with authorized generics, overall drug spending stays higher. The real savings-when generics drop to 10% of brand price-never happen.

Even the FDA’s own data shows that authorized generics are now less common than they used to be. In 2010, they appeared in 42% of markets with first-filer exclusivity. By 2022, that dropped to 28%. Why? Because regulators are watching. Lawsuits are piling up. And the FTC is making it clear: this isn’t competition. It’s manipulation.

What’s Changing? And What’s Next?

There’s pressure building. The FTC has opened 17 investigations since 2020 into authorized generic deals. In 2022, they declared that "agreements to delay authorized generic entry" are a top enforcement priority. Senator Amy Klobuchar and Chuck Grassley reintroduced the Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act in 2023. If it passes, it would ban companies from using authorized generics as a tool to delay competition.

Some experts argue authorized generics increase supply. But supply doesn’t matter if the price doesn’t drop. The real test is: does the patient pay less? In most cases, the answer is no.

What’s more, the data shows that when authorized generics are expected, fewer generic companies even bother challenging patents. For drugs with low sales-under $27 million a year-the risk isn’t worth it if the brand can just launch its own generic and crush the first filer. That’s not innovation. That’s deterrence.

Why This Matters Beyond the Pharmacy Counter

This isn’t just about pills. It’s about trust in the system. The Hatch-Waxman Act was built on a promise: if you challenge a patent, you get a shot at the market. That promise is being broken. And patients are paying the price-in dollars, in delayed access, in higher premiums.

When a company can legally copy its own drug and use it to block competitors, the whole idea of competition collapses. It turns a system meant to lower prices into a game of legal chess where the house always wins.

The solution isn’t to ban generics. It’s to ban the tricks that keep them from working. Authorized generics should be allowed-but not when they’re used as weapons in patent settlements. Not when they’re priced like brand drugs. Not when they’re part of a deal to silence real competition.

The system still has a chance to fix itself. But it won’t unless regulators, lawmakers, and the public keep asking: Who really benefits when a brand company sells its own drug under a generic label?

Reviews