Opioid Risk Assessment Tool

Personal Risk Assessment

This tool helps identify your risk of opioid-induced respiratory depression based on factors discussed in the article.

When someone takes an opioid - whether it's oxycodone, fentanyl, morphine, or even a prescription painkiller - their breathing can slow down. Not just a little. Enough to stop. And sometimes, it happens quietly, without warning. This isn’t a rare accident. It’s a predictable, preventable medical emergency called opioid-induced respiratory depression (OIRD). Every year in the U.S., around 20,000 people need naloxone just to breathe again after their breathing shuts down from medication. Most of them weren’t using drugs recreationally. They were following their doctor’s orders.

What Does Respiratory Depression Actually Look Like?

It doesn’t always look like someone passed out on the couch. Early signs are subtle, easy to miss. You might notice someone breathing slower than usual - fewer than 10 breaths per minute. That’s not tiredness. That’s your brain’s breathing control center being suppressed. Their breaths become shallow, like they’re barely filling their lungs. Sometimes they’re irregular - a few quick breaths, then a long pause. In severe cases, breathing stops for 10, 20, even 30 seconds at a time.

Here’s what clinicians look for: respiratory rate below 8 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation under 85%, and a lack of response to rising carbon dioxide levels. These aren’t guesses. They’re measurable thresholds backed by clinical studies. The problem? Supplemental oxygen can hide the danger. Someone might have 95% oxygen saturation on a pulse oximeter - but their blood is drowning in CO2. Their body isn’t blowing off the gas. Their brain isn’t telling them to breathe harder. That’s when things turn critical.

Who’s at the Highest Risk?

Not everyone reacts the same way. Some people can take high doses and stay alert. Others slip into respiratory depression after one pill. Risk isn’t random. It’s predictable if you know the signs.

- People over 60 - their bodies process drugs slower, and their respiratory centers are more sensitive.

- Women - studies show they’re 1.7 times more likely to develop OIRD than men, even at the same dose.

- Opioid-naïve patients - those who’ve never taken opioids before. Their bodies haven’t built tolerance. One dose can be enough.

- People taking other CNS depressants - benzodiazepines like Xanax or Valium, alcohol, sleep aids, muscle relaxers. Combine opioids with any of these, and your risk jumps 6 to 14 times higher.

- Those with multiple health conditions - COPD, sleep apnea, heart failure, kidney disease. Each additional condition raises risk by nearly 3 times.

One study found that patients with just two of these risk factors had a 47% higher chance of developing severe respiratory depression. That’s not a small number. That’s half the time.

The Silent Danger: When Monitoring Fails

Hospitals check vital signs every four hours. That means a patient is unmonitored 96% of the time. In that window, breathing can slow, then stop. Pulse oximeters are common, but they’re not enough. If someone is on oxygen, the device might show normal oxygen levels even as CO2 builds to dangerous levels - 50 mmHg or higher. That’s when brain damage starts.

Capnography - the device that measures carbon dioxide in exhaled breath - is far more accurate. It catches problems before oxygen drops. But only 22% of U.S. hospitals use it routinely for non-intubated patients on opioids. Community hospitals? Only 14%. Meanwhile, alarm fatigue is real. Nurses hear so many false alarms that they start ignoring them. One survey found only 42% of nurses could correctly identify early signs of respiratory depression in a simulation.

What Happens If You Don’t Act?

Untreated respiratory depression doesn’t end in a hospital bed. It ends in brain damage - or death. When breathing stops, oxygen stops reaching the brain. After three minutes without oxygen, brain cells begin to die. After ten, recovery is unlikely. And it happens faster than you think. In one case, a 72-year-old man on post-op morphine was found unresponsive 30 minutes after his last dose. He’d stopped breathing. He was revived with naloxone, but suffered permanent memory loss.

Even if someone survives, the aftermath is brutal. Withdrawal from naloxone can trigger intense pain, anxiety, and agitation - especially in cancer patients who need pain control. Giving too much naloxone too fast can turn a controlled pain management situation into a crisis.

How to Prevent It - and What Works

Prevention isn’t about avoiding opioids. It’s about using them safely.

- Check opioid tolerance before giving any dose. Never assume someone can handle a standard dose.

- Avoid fixed-schedule dosing for opioid-naïve patients. Give small amounts, then wait.

- Use continuous monitoring for high-risk patients - especially those with two or more risk factors.

- Never combine opioids with benzodiazepines, alcohol, or sedatives unless absolutely necessary - and even then, reduce the dose by 50%.

- Implement mandatory 2-hour post-dose monitoring for anyone new to opioids or with risk factors.

Hospitals that did this saw a 47% drop in OIRD cases. That’s not theory. That’s real data from leading medical centers.

The New Tools - And Why They’re Still Not Enough

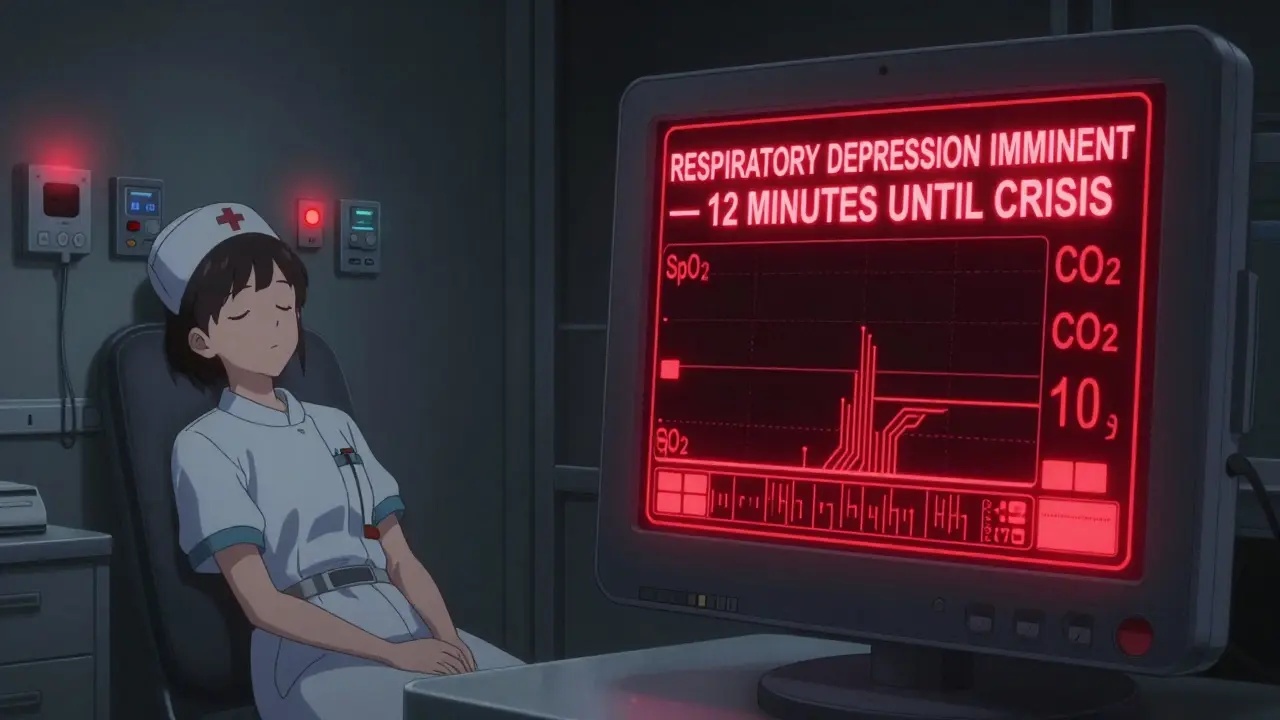

Technology is catching up. In January 2023, the FDA approved the Opioid Risk Calculator (ORC), which uses 12 factors - age, weight, kidney function, drug history, comorbidities - to predict an individual’s risk with 84% accuracy. Some smart monitors now combine pulse oximetry, capnography, and AI to predict respiratory depression up to 15 minutes before symptoms appear.

But here’s the catch: these tools only work if hospitals use them. And most don’t. The cost of equipment, staff training, and protocol changes is high. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) now classifies severe OIRD as a "never event" - meaning hospitals get penalized if it happens. That’s pushing change, but slowly. The market for OIRD monitoring tech has grown from $287 million in 2020 to $412 million in 2023. But growth doesn’t equal adoption.

What You Can Do - Even If You’re Not a Doctor

If you’re caring for someone on opioids - at home or in a facility - learn the signs:

- Slow breathing (less than 10 breaths per minute)

- Shallow or irregular breaths

- Unresponsiveness or confusion

- Lethargy, dizziness, nausea

- Lips or fingertips turning blue

Keep naloxone on hand if someone is at risk. It’s available without a prescription in most states. Know how to use it. Call 911 immediately - even if naloxone works. The effects wear off faster than the opioid, and breathing can stop again.

Don’t wait for someone to pass out. If you notice any of these signs, act. Talk to their doctor. Ask if they’ve been assessed for risk. Push for monitoring. Your intervention could save a life.

Why This Matters More Than Ever

Opioid-induced respiratory depression isn’t a side effect you can ignore. It’s the leading cause of preventable death in post-op patients. It’s not just about addiction. It’s about pain management gone wrong. About systems failing. About well-meaning people giving the right drug at the wrong time.

The good news? We know how to stop it. We have the tools. We have the data. We just need to use them.

Every person on opioids deserves to be monitored. Every family deserves to know the signs. And every healthcare provider needs to treat respiratory depression like the emergency it is - not an afterthought.

Can you have opioid-induced respiratory depression without using street drugs?

Yes. In fact, most cases happen in hospitals or at home after prescribed opioid use. People taking oxycodone for back pain, morphine after surgery, or fentanyl patches for chronic pain are at risk - especially if they’re elderly, on other sedatives, or haven’t taken opioids before. It’s not about illegal drug use. It’s about how the body reacts to the medication.

Is naloxone safe to use if I’m not sure it’s an overdose?

Yes. Naloxone only works on opioids. If someone is breathing slowly due to opioids, naloxone will reverse it. If it’s something else - like a stroke or seizure - naloxone won’t hurt them. It has no effect on non-opioid drugs. Giving naloxone when you’re unsure is the right call. Better to reverse a potential overdose than wait too long.

Can supplemental oxygen prevent respiratory depression?

No. Oxygen keeps blood oxygen levels up, but it doesn’t fix the root problem: the brain isn’t signaling the lungs to breathe. The person may still have dangerously high carbon dioxide levels, which can lead to coma or death. Oxygen can mask the warning signs, making it harder to detect the problem early.

What should I do if someone on opioids becomes unresponsive?

First, check for breathing. If they’re not breathing or breathing very slowly, call 911 immediately. Give naloxone if you have it. Start rescue breathing if trained. Don’t wait for EMS to arrive. Every minute counts. Even if they wake up after naloxone, stay with them - the opioid can reassert itself as naloxone wears off.

Are there any new medications that don’t cause respiratory depression?

Researchers are developing biased mu-opioid receptor agonists that relieve pain without suppressing breathing. These are in late-stage clinical trials and show promise. But they’re not available yet. For now, the safest approach is using existing opioids with strict monitoring, proper dosing, and avoiding combinations with other sedatives.

Reviews

Let me tell you something that keeps me up at night: hospitals are treating opioid safety like a suggestion, not a standard. I work in a trauma unit, and I’ve seen patients coded because their pulse ox showed 98% while their CO2 was at 72. They were on morphine, on oxygen, and their nurse checked vitals every four hours. Four hours. That’s not monitoring. That’s gambling with a life. Capnography isn’t fancy-it’s essential. If your hospital doesn’t have it, demand it. Or better yet, don’t let your loved one be alone in that bed after surgery.

My grandma was on a fentanyl patch after her hip replacement. She was 82, had COPD, and was on a sleep aid. The nurse said, ‘She’s fine, her oxygen’s good.’ But I noticed she wasn’t answering when I called her name. I grabbed the naloxone we kept in the fridge-yes, we kept it at home-and gave her a dose. She gasped awake. Turned out her breathing had dropped to 6 per minute. They didn’t even check her CO2. I’m not a doctor, but I know this: if you’re caring for someone on opioids, learn the signs. Keep naloxone. Don’t wait for the system to save them. Save them yourself.

People think this is about addiction, but it’s not. It’s about lazy medicine. Doctors prescribe opioids like candy and then blame the patient when they stop breathing. No one wants to admit they didn’t do the math. No one wants to check for drug interactions. It’s easier to say ‘it was an accident’ than to admit you ignored the 12 risk factors on the checklist. This isn’t a tragedy-it’s negligence dressed up as protocol.

I just want to say thank you for writing this. My brother was prescribed oxycodone after his back surgery, and he was terrified to take it because he’d seen what happened to his uncle. He asked his doctor if he was at risk-he’s 64, has mild sleep apnea, and takes a low-dose beta blocker. The doctor just said, ‘You’ll be fine.’ He didn’t even ask about his meds. I cried when I read your list of risk factors. He’s now on gabapentin and physical therapy, and he’s pain-free and breathing fine. Knowledge saved him. Please keep sharing this. People need to hear it before it’s too late.

In India, we don’t have capnography machines in most rural clinics. We don’t even have pulse oximeters in some places. My aunt took morphine after a C-section and stopped breathing in the night. The nurse found her at 4 a.m. She survived, but her brain didn’t recover fully. We didn’t know about naloxone. We didn’t know breathing could stop silently. This isn’t just a Western problem. It’s a global silent killer. We need community education-posters in clinics, radio announcements, videos in local languages. If you’re reading this, share it with someone who cares for an elderly parent. This could be their lifeline.

There’s a philosophical paradox here: we’ve created drugs that relieve suffering by suppressing the very mechanism that sustains life. The body’s instinct to breathe is overridden by a molecule designed to silence pain. Isn’t that the ultimate irony? We seek to remove suffering, but in doing so, we risk extinguishing the breath that makes suffering bearable. We’ve engineered a solution that demands more vigilance than the problem it solves. Maybe the real question isn’t how to monitor better-but whether we should be prescribing this at all, unless absolutely necessary.

Capnography is expensive. That’s why it’s not used. But the real reason? Hospitals don’t want to admit how many people they kill with opioids. The FDA calls it a ‘never event’-but they still approve new opioids every year. This is corporate medicine. Profit over pulse. If you think naloxone is the answer, you’re missing the point. The system is broken. The data is there. The tools are there. But the will? Nonexistent.

So let me get this straight: you’re telling me that if I’m on a fentanyl patch and take a Xanax for anxiety, I’m 14 times more likely to stop breathing? And the hospital won’t even monitor me? And the nurse might ignore the alarm because she’s heard 40 false ones today? And I’m supposed to trust this system? 😂👏👏👏

Bro, I’m not dying for a painkiller. I’m taking ibuprofen and yoga. And if I have to take opioids? I’m bringing my own capnograph. And a megaphone. And a lawyer.

As a medical professional in India, I can confirm that the issue is not only systemic but also cultural. Families often hesitate to question doctors. They believe silence equals compliance. They do not know that slow breathing is not rest-it is a warning. We have launched awareness campaigns in local languages, distributing pamphlets with visual guides on breathing patterns. We teach families to count breaths for 15 seconds and multiply by four. If it’s under 10, they call for help. No waiting. No doubt. This simple step has saved lives in villages where hospitals are hours away. Education is the first line of defense. Not technology. Not policy. People.

I’ve been a nurse for 27 years. I’ve seen too many patients slip away because no one was watching. I’ve also seen families who learned the signs and saved their loved ones. This isn’t about blame. It’s about empowerment. If you’re caring for someone on opioids, you’re not just a caregiver-you’re a lifeline. Learn the numbers. Keep naloxone. Speak up. Even if you’re not a doctor. Even if you’re scared. Your voice matters more than you know. And if you’re a provider? Listen to the family. They see the changes before the charts do.